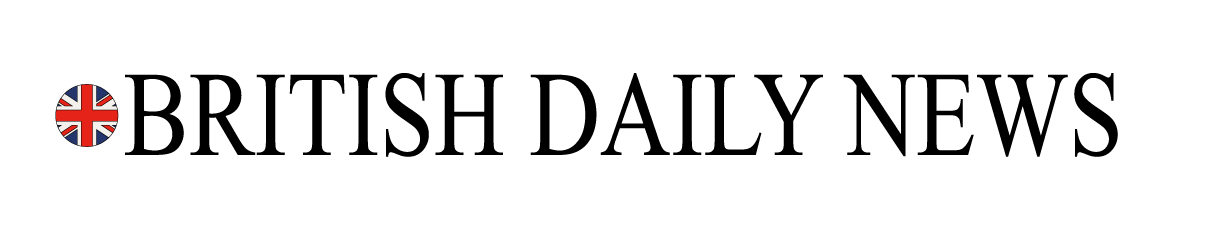

The best film! Of all the awards, this is the one most drenched in glory – and hubris. It comes at the end of a long night, and it’s the one most keenly anticipated by the producers themselves who now have their moment of glory as the people for whom this award represents years of agonising work and instances of what Jerry Maguire called the “up-at-dawn pride-swallowing siege that I will never fully tell you about”. For the winner, it is a moment of euphoria and exhaustion, which last year Warren Beatty did his best to make as chaotic as possible, with Faye Dunaway, by accidentally awarding best picture to La La Land, when it should have gone to Moonlight. It is a measure of the suppressed hysteria that Oscar night engenders that this egregious cockup is the subject of its very own “truther” conspiracy – a theory that it was deliberately contrived to boost ratings. Looking down the list, it is disconcerting to see how many favourites and classics were not in fact rewarded with the best picture statuette. But there are quite a few that are, and here are some mouthwatering examples.

Rebecca

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca was the great man’s Hollywood debut; he was brought to the US by the shrewd David O Selznick, who effectively placed a crown on his head. The movie is stylishly adapted from the Daphne du Maurier novel by Robert E Sherwood and Joan Harrison. It is a gripping romantic mystery with superb performances from Joan Fontaine and Laurence Olivier — and an influence, incidentally, on Paul Thomas Anderson’s new film Phantom Thread. Olivier is the saturnine widower Max de Winter who marries Fontaine’s shy and mousy lady’s companion and brings her back to his magnificent Cornish home, which is all but haunted by his first wife: Rebecca. There is a terrible secret in this house, connected to the creepy housekeeper, Mrs Danvers, unforgettably played by Judith Anderson.

Casablanca

Virile, passionate, patriotic: these adjectives apply to the male lead of Michael Curtiz’s Casablanca, as well as to the movie itself. It is that rare beast: a second world war picture that came out in the middle of the war, when the outcome of the war in Europe was far from clear. Humphrey Bogart is Rick, the tough American bar-owner in Vichy-controlled Morocco, secretly nursing a broken heart. Of all the gin joints, she has to walk into his – Ilse, played by Ingrid Bergman, the resistance leader’s wife he fell in love with in Paris, when the Nazis were moving in. The movie’s fierce anti-Nazi ethic is glorious, the dialogue crackles along and the romance is gorgeous. Find yourself watching the opening moments on TV and you have to stay to the end, no matter how often you’ve seen it before.

On the waterfront

With its sheer artistry, muscular idealism, and the passionate intensity of the acting — along with Leonard Bernstein’s bright, clamorous orchestral score — Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront is a true classic. Marlon Brando’s wonderfully uninhibited performance set a gold standard for the new method style of acting. He and the movie in general are an obvious inspiration for Scorsese’s Raging Bull. Brando is Terry Malloy, a washed-up boxer now casually employed at the docks – a crooked closed shop controlled by mobster union boss Johnny Friendly (Lee J Cobb). Terry has a cushy deal taking pay for no work, because he’s the kid brother of Friendly’s top consigliere, Charley Malloy (Rod Steiger). But people who talk to the cops get whacked and Terry is secretly sickened by the murders that he has connived at – and at the way his brother betrayed him at the beginning of his boxing career. Hollywood history has given this film a patina of tragedy and irony: Terry wonders if he has the moral courage to name names for the authorities and later, Kazan would be pilloried for doing that during the McCarthyite era. At any rate, On the Waterfront is an operatic masterpiece.

The apartment

Romantic comedy is a genre now synthesised and commodified into something very predictable. But Billy Wilder’s The Apartment is a masterly mix of material that is both funny and romantic – with a uniquely charming and accessible male lead in Jack Lemmon. He is the put-upon salaryman in New York who has been bullied by his boss into lending out his apartment for this sleazebag’s extramarital liaisons. Meanwhile, he is falling in love with a heartbreakingly pretty elevator operator, played by Shirley MacLaine. It’s a smart and sophisticated big-city satire with a heart of authentic gold.

The Godfather

Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather was the high point of the American new wave and revived the reputation of Hollywood itself. Like Spielberg’s Jaws, it brilliantly took a pulpy format and supercharged it with meaning and intensity. Brando is the ailing Vito Corleone, presiding over a postwar mafia clan; his sons are coming to terms with what their own destinies are to be when he goes. Al Pacino is Michael Corleone, the decorated war veteran who appears to want nothing to do with his toxic family inheritance. The secrecy, the dysfunction, the fear and self-hate which is transformed into fanatical dedication – it is all here. The mafiosi behave like soldiers in a war movie, only it is peacetime and the battle is on home soil. A magnificent achievement, aspiring to an almost Shakespearean grandeur.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

Kirk Douglas played the role on Broadway, but when it came to the movie version, his producer son Michael took the decision to cast the young hotshot Jack Nicholson and the rest is film history. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest was directed by Milos Forman and adapted by Lawrence Hauben and Bo Goldman from the Ken Kesey novel. Nicholson plays Mac McMurphy, a small-time crook sent down for statutory rape who by playing up his natural craziness gets what he thinks is a cushy transfer to a psychiatric facility, where he leads a revolt of the patients against the system. A fascinating film, soaked in the anti-establishment zeitgeist. Louise Fletcher gives a great performance in the chilling, but complex role of Nurse Ratched.

Annie Hall

This is a difficult time to be remembering the brilliance of Woody Allen’s Annie Hall. Objection to his personal life has reached a critical mass, largely due to the recent TV interview that Dylan Farrow gave, effectively introducing a new generation to her original abuse allegations from 1992. However, no legal proof has been established, and Moses Farrow has crucially offered his own complicating testimony. It could be argued that, whatever we think, the reputation of Allen has now been so clouded that, like it or not, Annie Hall has ceased to be funny. I personally think it would be absurd now to airbrush this film out of history and behave as if we never had time for it. It is his fictionalised account of his lost romance with Diane Keaton, and it is a film that pretty well invented the relationship comedy, as well as giving birth to Seinfeld, Curb Your Enthusiasm and Girls. And it’s an ancestor of the work of Charlie Kaufman. Annie Hall has lost its innocence, but not its brilliance.

Schindler’s List

Schindler’s List was a powerful and deeply honourable film for Steven Spielberg, an adaptation of the Thomas Keneally book, and an intensely felt attempt to find the possibility of hope in the very heart of darkness itself: the Nazi concentration camp. It is the true story of the German businessman Oskar Schindler, played with dignity and presence by Liam Neeson, a mercenary cynic who entered a mysterious state of grace and saved over a thousand Jews from death. The young Ralph Fiennes plays the unspeakable camp commander Amon Goeth and Ben Kingsley is Schindler’s bookkeeper Stern. The emotionally exhausting three-hour-plus movie is throughout (mostly) in black-and-white, often using handheld shots with Spielberg in personal charge of the camera.

No country for Old men

Cormac McCarthy’s apocalyptic western thriller No Country for Old Men was filmed with passion and style by the Coen brothers: a dark and disquieting Texan movie to compare with their debut, Blood Simple. Tommy Lee Jones is the impassive sheriff, who sets off on the trail of the good ol’ boy (Josh Brolin) who has chanced upon and fled with a bag of $2m of criminals’ money. On his trail also is the deeply creepy killer tasked with recovering this loot for the bad guys: the bizarre Anton Chigurh, played by Javier Bardem. It’s bleakly funny and exciting, but also terrifying in its presentiments of pure evil.

Moonlight

Bizarre announcement cockups from Beatty and Dunaway to one side, Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight is a remarkable Oscar achievement: a film of real artistry and form, combined with emotional power. It’s a triptych portrait of a young gay black man, played by three different actors as a kid, a teen and then a young man: an almost Tolstoyan sense of childhood, boyhood and youth. Moonlight is about the nature of masculinity, conditioned by the determinant factors of race, class – and sexuality. Its rendering of time and the vicissitudes of identity are complex and enigmatic, but deeply moving at the same time.

Source https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/mar/01/what-is-the-best-oscar-winning-film-of-all-time-casablanca-the-godfather-moonlight