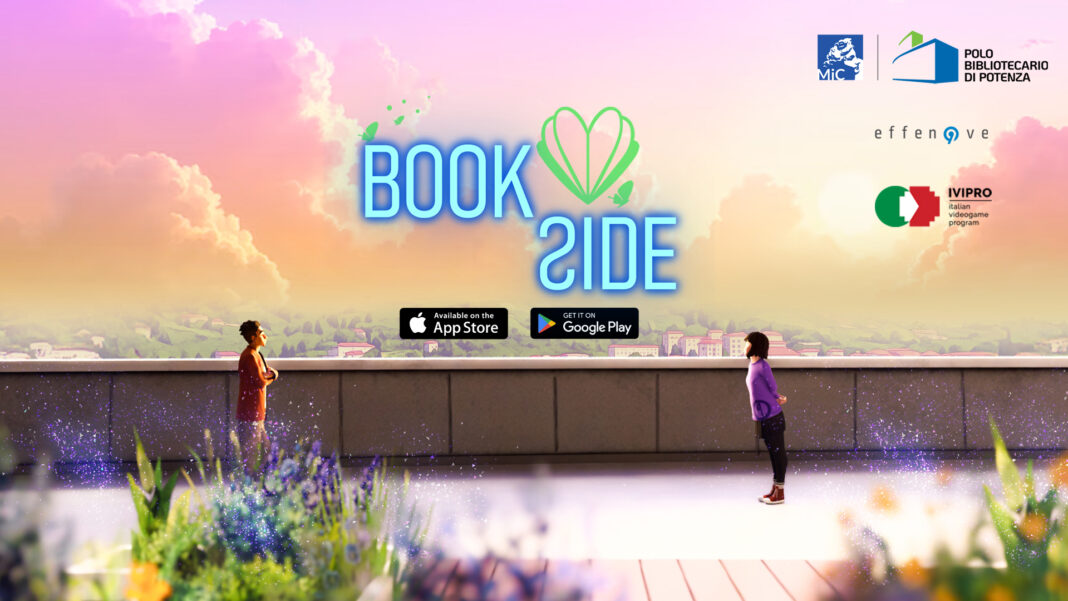

What do a library and a video game have in common? More than one might think. Both are spaces of exploration, places where you move through levels, discoveries, detours, and returns. From this insight comes Book Side, the smartphone platform game conceived and developed by Effenove srls, a 3D computer graphics company based in Potenza, in collaboration with the Potenza Library Hub — the home of culture established through a Memorandum of Understanding between the Italian Ministry of Culture, the Basilicata Region, and the Province of Potenza. Not a game set in a library, but a library that becomes a playful experience: corridors, reading rooms, archives, and workshops are transformed into an interactive map, a true open world of knowledge in which the reader-player does not merely observe but acts. “We wanted to make visible what the library already is: a living space, one that can be crossed and experienced, rich in relationships,” says Michele Scioscia, co-founder of Effenove. Luigi Catalani, Director of the National Library of Potenza (Ministry of Culture) and of the Library Hub, explains the deeper meaning of the project: “Inspired by Saint Augustine’s words, ‘Only what delights the mind truly nourishes it,’ we are proud to be the first Italian library to take center stage in a video game. We believe in the cultural, educational, and social value of play and video games as narrative devices capable of enhancing bibliographic heritage and the relationships among the people who inhabit our spaces.” Presented at IVIPRO Days 2025 within the framework of the Trieste Science+Fiction Festival, Book Side contributes to the international debate on video games as tools for narrating cultural heritage and places of knowledge through contemporary languages.

Engineer Scioscia, Book Side stems from a simple yet ambitious question: can a video game tell the story of a library?

Yes — if we accept that a library is not merely a place of preservation, but a living space. We were inspired by a very clear cultural vision: knowledge truly works when it engages, when it moves people emotionally. In this sense, play does not trivialize — it activates. Book Side was created to allow people to discover the library as an experience, not as a backdrop.

You didn’t create a video game “about” a library, but a library that can be played. Why?

Because we wanted to avoid any superficial form of gamification. The library is already a complex map: made of paths, levels, and relationships. We simply translated this structure into the language of gaming, preserving its cultural and social value intact.

How important was the work on the real physical space?

It was fundamental. Everything begins with observing and respecting the place. We recreated the environments through drawings, 3D modeling, and interactive programming, turning furniture, corridors, and services into gameplay elements. In this way, players move from the archives to the FabLab, where books, digital technologies, coding, and educational robotics naturally coexist.

Books become worlds to explore. How did you choose them?

The selection is the heart of the project. Each book was translated into recognizable environments and symbols without losing its identity. The journey unfolds across five stages of love: from the letters of Léon Bloy to the geometries of Albert Friscia, from the poetry of Isabella Morra to the graphic novel of Alessandro Baronciani, and finally to the gaze upon nature in Orazio Gavioli’s Herbarium. We didn’t just want people to read the books — we wanted them to live them.

What role do you believe video games play in contemporary culture?

A fully legitimate one. Video games are powerful narrative devices, capable of creating relationships, memory, and a sense of belonging. When used responsibly, they can enhance cultural heritage and engage new audiences — especially younger generations.

Are you already looking beyond Book Side?

Yes. We are currently working on an interactive map for visits to Villa Farnesina in Rome, in collaboration with the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei. There too, the goal is not to digitize art, but to restore time to it — the time needed to observe, listen, and truly understand.

In conclusion, what message would you like to share?

That cultural institutions can speak new languages without losing their identity. Book Side shows that innovation does not mean simplification, but rather creating new opportunities for encounters between people and knowledge.